News

- Dave Winfield is getting a statue dedication … in Alaska

The Hall of Famer once hit a monstrous homer off a Fairbanks curling club

May 1st, 2024

Matt Monagan (@MattMonagan)

During his 22-year playing career, Dave Winfield made milestones all over North America.

He made his first All-Star Game while playing in San Diego. He won a World Series in Toronto. He notched his 3,000th hit in his home state of Minnesota. He earned a Hall of Fame plaque in Cooperstown.

But as his peers routinely remind him, Winfield never got a statue in any one of these places. Not in his hometown of St. Paul. Not in San Diego, where fans overwhelmingly support one. Not in any of the five other cities he made his home during his decorated baseball life.

Eventually, Fairbanks, Alaska, got word of Winfield’s missing distinction: A town where a college-aged Winfield once mashed a 500-foot home run off the building of a curling club. And this week, the town announced it will be presenting the Hall of Famer with a giant bronze likeness of his own.

“As we’re talking now, when I was 18 or 19 years old, I never imagined that people would still recall, remember, document what I did,” Winfield said in a press conference on Tuesday. “To be honored like this, it’s a wonderful thing. I look forward to bringing my family to a place that really made a difference in my life.”

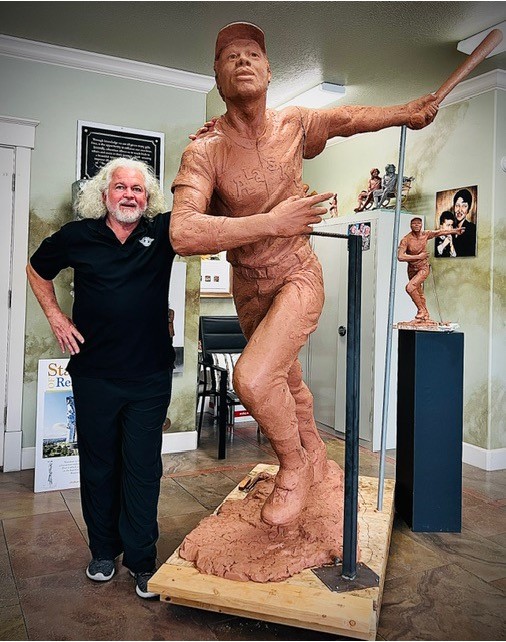

Sculptor Gary Lee Price with the clay version of the Dave Winfield statue. Yes, for a couple of memorable summers during his years at the University of Minnesota, Dave Winfield played for the Alaska Goldpanners of Fairbanks. A team, and a league, where a young Barry Bonds, Randy Johnson and Bill “Spaceman” Lee once roamed.

Winfield took pontoon planes out to secluded lakes to catch enormous pike, he lived in a small log cabin with a host family and he worked at a local furniture store — pulling lamps and chairs off the shelves for customers. That is, until, he urged the coach to place him somewhere a bit safer.

“I said, ‘Coach, man, I need an executive position,'” Winfield laughed. “‘I got a $100,000 arm,’ I remember telling him. So, the next year I went up there, I cut the grass and lined the field which was right behind the home that I stayed at.”

Amazingly, for a guy that ended up compiling more than 450 home runs and 3,000 hits in his big league career, Winfield’s college coach only saw his 6-foot-6, 200-pound star athlete as a pitcher. He wouldn’t hit at Minnesota until his senior year. But during that first summer in Alaska, after some urging from Winfield and a few great BP sessions, renowned coach Jim Dietz gave him a shot. Fairbanks is where his career “took a turn” and he became the hitter we all knew during his MLB days.

He put up some good numbers at the plate for the Goldpanners, but his most famous moment — the one depicted in the statue and still remembered in the 32,000-person town so many decades later — is a giant home run over the left-field fence. More than 50 years later, Winfield tells the story of the long ball like it happened yesterday. He was put in to hit for Bob Boone, who had been signed by a big league club.

“I was put in to pinch-hit,” Winfield recalled. “The bases were loaded. The pitcher pitching to me fell behind, three balls, no strikes. The manager for the other team walked almost to the baseline and told the pitcher, ‘Throw the ball over the plate, he’s just a pitcher!’ Shouldn’t have done that. Next ball was a fastball and it started high and left the ballpark high.”

“If you go to Google Earth and you use the measurement tool, you’ll get 480 feet,” Lance Parrish, a Fairbanks community leader who first initiated the statue idea, said. “If it hit the bottom of the curling club or hit the top, it’s over 500 feet. So, it’s somewhere between 480 and 500 feet. But the distance was never the legend. That it hit the curling club was the legend. And it was a legend. It’s the first thing that came to my mind when [Winfield] was being teased for not having a statue.

Photo via Google Maps “I knew that I had to capture the energy,” Price said of his statue and the home run. “You have an inanimate object that somehow has to have this motion and energy behind it. I wanted to capture, kind of the follow-through. You know, which is the vision. That part where Dave is looking up. Like Dave said, ‘It started out high and it kept going high.’ That’s what I wanted to capture. And it was just an honor to be able to get it to that point where, when we showed it to Dave and his representative, and they said, ‘Yup, that’s it.’ Yes, home run, baby.”

The 8-foot tall, 500-pound statue will, quite appropriately, be placed near its landing spot at the foot of the still-existing Fairbanks Curling Club. There will be a special unveiling ceremony before this June’s Midnight Sun Baseball Game — a “high noon at midnight” classic that’s been played without any artificial light for the last 119 years. Winfield will be in attendance with his family and will deliver the game’s ceremonial first pitch.

“I look forward to going back to Alaska,” Winfield said. “Like I said, it was a turning point in my baseball career. An enjoyable time in my life. I look forward to this summer.”

- Dave Winfield To Appear At City’s Annual BRAVO Awards

The City of Bellflower is proud to recognize a total of 10 first responders and public safety

personnel for extraordinary acts of heroism and outstanding service at the 28th annual

BRAVO Awards ceremony and luncheon on Thursday, April 25, 2024.

Two student essay award winners will also be awarded $500 sponsorships at the event,

which takes place at The Mayne Events Center, located at 16400 Bellflower Boulevard. The

program is sold out and there are no available tickets for purchase.

National Baseball Hall of Fame inductee, Dave Winfield, will serve as our special Keynote

Speaker along with other local dignitaries. Winfield ranks as the greatest multisport athlete

to emerge from the state of Minnesota. Dra!ed by five teams in five leagues in three major

sports, Winfield chose baseball and compiled a first-ballot Hall of Fame career. Winfield

jumped straight from college to the major leagues, playing a combined 22 seasons with the

San Diego Padres, New York Yankees, California Angels, Toronto Blue Jays, Minnesota Twins,

and Cleveland Indians. He appeared in 12 All-Star Games, two World Series, and was the fi!h

player in the history of baseball to get 3,000 hits and 450 home runs. We look forward to

welcoming Winfield to the City of Bellflower as we pay tribute to our local community

heroes.

The BRAVO Awards ceremony is funded through sponsorships from area businesses and

individuals and represents one of the City of Bellflower’s most prestigious honors. For info

on the BRAVO program, call (562) 804-1424 ext. 2267.

- Hall of Famer Dave Winfield honored with a mural near Yankee Stadium

JUSTIN PETRILLE MLBbro.com

On April 24, Hall of Famer and former Yankee Dave Winfield was honored with the unveiling of a mural bearing his image near Yankee Stadium. Credit: MLBbro Sign up for our acclaimed free newsletter Editorially Black with the top Racial Equity stories of the day to your inbox!

Heroes get remembered, but legends never die. New York Yankees MLBbros are being immortalized for heroics that have made them legends forever.

Dave Winfield was honored on April 24 for his incredible accomplishments while wearing the pinstripes with a mural a few blocks away from Yankee Stadium.

The mural, titled “Exhibiting Possibilities: Legendary Yankees,” was a collaboration led by The Bronx Children’s Museum, The Players Alliance, the Yankees and the Bronx Terminal Market to feature historically great Black Yankees players.

“We hope that every boy or girl that sees these murals will have their own dreams of greatness on the field and, more importantly, in their communities. We will continue to support the storytelling of excellence surrounding the Black players in our game, and we look forward to continuing to honor our history, particularly our history of Black players,” MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said during the unveiling of the mural.

An uber-athletic outfielder, Winfield played for the Yankees from 1981-1990, during which he was an All-Star for all but the last two seasons of his stint in the Bronx. He also won five Gold Gloves and five Silver Sluggers over his time as a Yankee.

Winfield played the first eight seasons of his career with the San Diego Padres, for which he is a member of the franchise’s Hall of Fame and has his No. 31 retired. The native of St. Paul, Minnesota was a standout for the University of Minnesota’s baseball and basketball teams before being drafted by four organizations in 1973: He was taken by the Padres with the fourth overall pick in the MLB draft, the Atlanta Hawks in the fifth round of the NBA draft and the ABA’s Utah Stars in the sixth round. And despite not playing college football, Winfield was a 17th round selection by the Minnesota Vikings in the NFL draft.

In addition to the Padres and Yankees, the 6-6, 225 pound Winfield also played for the Los Angeles Angels (formerly the California and Anaheim Angels), Toronto Blue Jays, Minnesota Twins and Cleveland Indians. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001 in his first year of eligibility. Winfield was the first Padres player ever to make it to the venerable HOF in Cooperstown, New York.

Even with the unforgettable accomplishments he had in his first 18 seasons with the Padres and Yankees, Winfield didn’t win a World Series title until 1992, in his one year with Toronto, when he was 41. During that season, he hit the game-winning, two-run double in the 11th inning of Game 6 of the World Series that clinched the title, forever earning him the nickname “Mr. Jay.”

Over the course of his career, Winfield, now 72, batted .283, with 465 home runs, 1,833 RBI, a career on-base percentage of .353, and a slugging percentage of .475. He also has 3,110 career hits, which is 23rd all-time. He was a 12-time All-Star, seven-time Gold Glove winner, and a six-time Silver Slugger award winner throughout the entirety of his playing career.

- Cracker Jack & Dave Winfield launch nostalgic exhibit at National Baseball Hall of Fame

Marketing can change the world.

By Audrey Kemp, LA Reporter

A new museum exhibit chronicles the snack brand’s shared history with the sport through ephemera dating back to 1914.

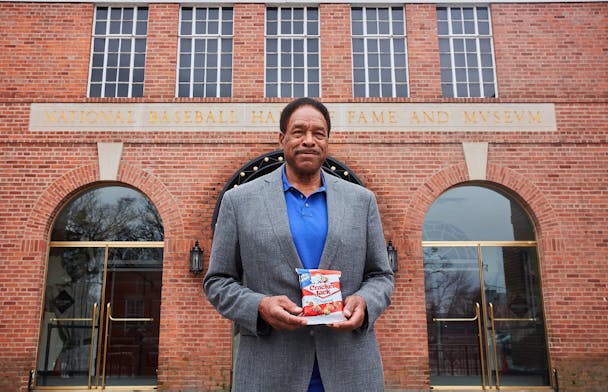

Dave Winfield holds a bag of Cracker Jacks outside of the National Baseball Hall of Fame / Credit: Frito-Lay

Baseball fans, grab your peanuts and Cracker Jack for a new exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

In a new partnership, Frito-Lay’s Cracker Jack has teamed up with baseball legend and Hall-of-Famer Dave Winfield to debut a new exhibit at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Titled ‘Cracker Jack at the Ballpark,’ the exhibit is a grand slam celebration of the snack brand’s historic connection to America’s favorite pastime. With Winfield as the honorary curator, the exhibit aims to score the right notes of nostalgia and fun.

“When I look back at my career, I’ll always cherish the energy that fills the stadium when fans take to their feet and sing out for Cracker Jack during the seventh-inning stretch,” Winfield said in a statement. “As an honorary curator, it is important to make sure that the exhibit reflects how special going to a game and enjoying Cracker Jack is to baseball fans.”

From the crack of the bat to the seventh-inning stretch, Cracker Jack has been a snack staple at ballparks for over a century. And now, fans can relive those magical moments with artifacts dating back to 1914, including classic baseball cards, signed memorabilia and a replica of the original hand-written lyrics to ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game.’

“No trip to the ballpark is complete without a visit to the concession stands, where Cracker Jack has reigned as one of baseball’s most popular snacks since the early 1900s,” said National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum president Josh Rawitch. “This exhibit honors the rich history and connection Cracker Jack has to the game and the heartfelt, nostalgic memories it evokes among baseball fans.”

As part of the launch, Cracker Jack is also hosting a sweepstake that offers one lucky fan (and three of their friends) the chance to win a VIP trip to Hall of Fame Induction Weekend 2024, from July 19 to 22.

To enter to win the grand prize and other weekly prizes, fans can visit www.CrackerJackHallOfFame.com or scan the QR code on the special-edition National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum packaging in stores for a limited time.

“Whether linking arms and singing during the seventh-inning stretch, flagging down vendors walking down the aisles or smiling ear-to-ear as you pull out the prize inside of our packaging, fans have felt the joy that Cracker Jack brings to baseball for decades,” added Leslie Vesper, vice-president of marketing, Frito-Lay North America. ”‘Cracker Jack at the Ballpark’ allows visitors of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum to once again experience those cheerful moments associated with both the brand and the sport.”

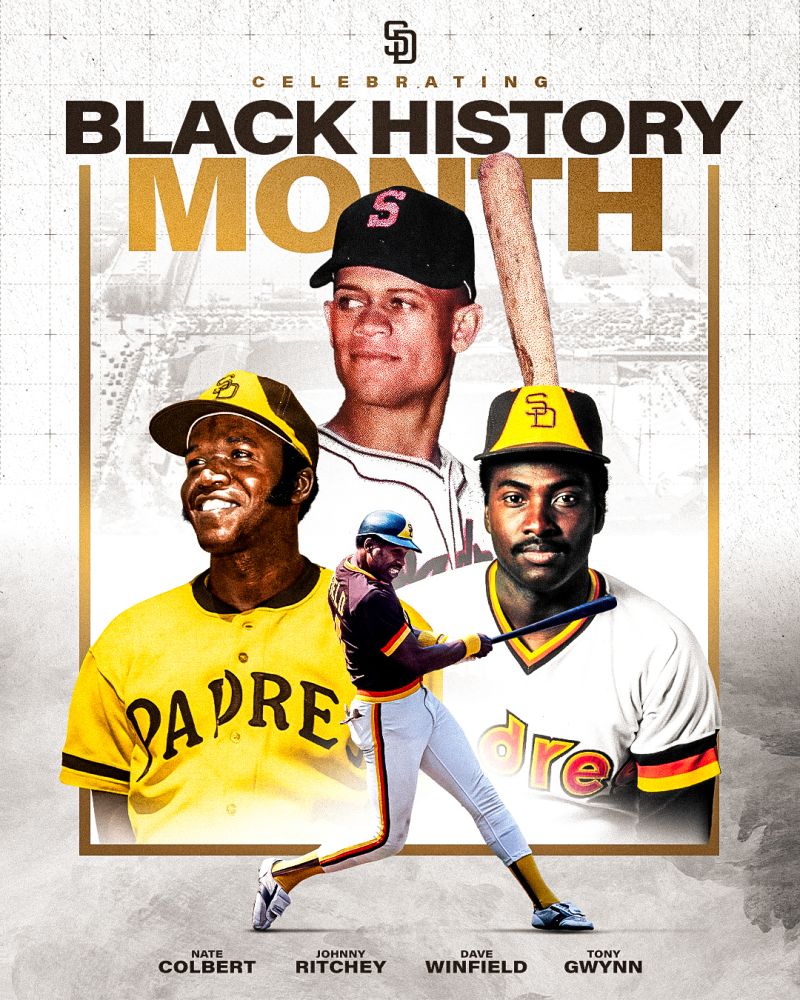

- San Diego Padres Celebrate Black History Month